Topic 3:

Earthlodge Features — The Central Channel and Air Deflector

Two interior features found inside Drover’s House are of particular interest because they are related to managing the air flow inside the lodge. One is the depressed central channel, and the other is an unmodified rock used as an air defector.

DEPRESSED CENTRAL CHANNEL

The depressed central channel is a floor feature that identifies Drover’s House as a classic Plains Village Type 1 house following the typology established by Panhandle research Christopher Lintz in his 1984 Ph.D. dissertation that was published by the Oklahoma Archeological Survey in 1986: Architecture and Community Variability within the Antelope Creek Phase of the Texas Panhandle. Studies in Oklahoma's Past No. 14. In this comprehensive study, Lintz examined the variability in architecture in the central portion of the Canadian River valley in the Texas Panhandle (basically the Lake Meredith stretch of the river). He devised a typology of structures and storage pits that is still the most comprehensive treatise on Antelope Creek architecture. Based on this research, Lintz defined the Antelope Creek Phase.

Lintz (1986:89–102) defined the Type 1 house as rectangular pithouses that were oriented to the cardinal directions, usually with an extended entryway on the east side. They commonly had walls lined with rock slabs both with and without evidence of associated postholes. Less commonly, Type 1 houses might have no wall rocks, and the walls were simple lines of vertical posts. Most Type 1 houses had interior roof support posts, ususally four. Lintz also notes that one of the most diagnostic features of the Type 1 house is the “presence of a depressed floor channel extending from the east to west wall through the central portion of the unit” and a central fire pit was located inside this channel (Lintz 1986:89).

Christopher Lintz’s 1984 dissertation was published by the Oklahoma Archeological Survey in 1986. While quite a bit of new archeological evidence has been discovered and reported across the Texas and Oklahoma Panhandles since this study was published, it remains the most comprehensive examination of Plains Village period architecture in the Southern Plains.

Plan view of the generalized “Type 1” Antelope Creek house as defined by Christopher Lintz in his 1986 publication: Architecture and Community Variability within the Antelope Creek Phase of the Texas Panhandle. The plan view shows that the central “channel” that runs the full length of the house, and covers the middle one-third of the house. The profile has been added to show the elevation differences between the benches and the depressed central channel. The depth of the central channel varies but is usually between 6 and 12 inches.

Three houses in Erickson’s West Pasture—Hank’s House, Drover’s House, and Pete’s House—fit Lintz’s (1986) model of classic Type 1 houses for the Antelope Creek Phase. These three houses have the diagnostic depressed central channel that runs through the center of the house, encompassing about one-third of the total interior floor space.

Plan view of the excavated half of Hank’s House, with the plan projected to include the missing north half of the house that was eroded away. Note the four central roof posts, the central fire pit, and the central channel. The gray shaded pattern outlines the curb edge of the side benches that drop down into the central channel. This map is from Hank’s House 1: Anatomy of a Burned Pithouse in the Plains Villagers of the Texas Panhandle exhibit on Texas Beyond History (see www.texasbeyondhistory.net).

Comparison of Lintz (1986) Type 1 house plan (top) and the generalized plan view of Drover’s and Pete’s Houses (bottom). Note the “channel” that runs down the center of these houses. Note that the circles representing the wall posts in the bottom drawing are stylized. They do not represent actual mapped post hole locations. This image is reproduced from Figure 7 in Frederick (2017).

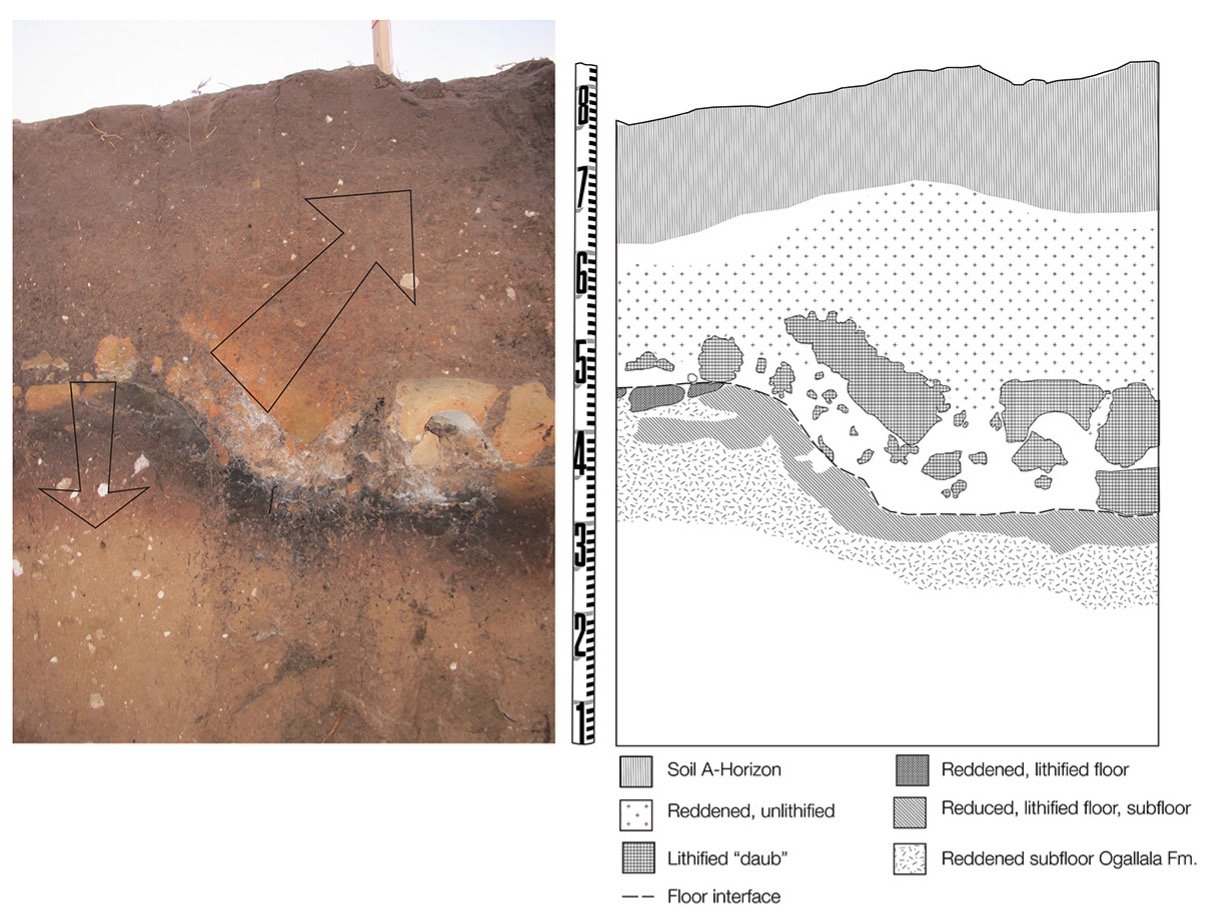

Photograph and diagram of a section of floor in Drover’s House. This view shows the contact between the burned floor plaster and the overlying layer of fired daub, charcoal staining, and heat-altered sediment—a.k.a., the collapsed roof material. This view also shows the point where the bench floor level drops down into the channel floor level. Reproduced from Figure 10 in Frederick (2017).

The presence of the central channel in the West Pasture houses is significant because this feature is unique to houses in the Antelope Creek Phase area and the western Canadian River valley in the Texas Panhandle. All other features for of the Type 1 house are seen, to some extent or another, in other culture areas to the north and west, the central depressed channel may well be a culturally diagnostic attribute specific to one or two groups of people.

AIR DEFLECTOR

Context is important concept in archeology. In the West Pasture, context helps us understand whether large rocks found in archeological sites represent natural occurrences or were brought in by people to serve some specific purpose. Caliche boulders and sandstone slabs occur naturally in various places in the West Pasture, but when they occur within an archeological site, it is their precise context (i.e., spatial relationships with other artifacts and features) that often reveals how people were using them. In a Plains Village setting, large rocks may be used in a variety of ways, such as for shoring or stabilizing architectural elements (e.g., wall rocks), as location markers (e.g., to mark a burial cairn or the top of an underground storage pit), as anvil stones, and for delineating boundaries.

One unusual rock found inside Drover’s house displays no modifications, but its context indicates that it had a very specialized function. It is a trapezoidal-shaped sandstone slab that was discovered 30 cm northeast of the north edge of the central hearth. The slab’s dimensions are: 5 cm thick, 28 cm long and 24 cm wide tapering to 15 cm. The slab was set almost vertically, with its narrow end buried below the floor level. Most of the slab was above the floor, and it there is little doubt that it was intentionally placed in this location. Located near the front of the lodge and just off-center, it is logical to assume that and served as an air deflector for the heath. Inside the lodge, there would have often been a predominant path for air being drafted into the entryway and out the smoke hole. A vertical slab placed strategically close to the central hearth would have protected the fire from wind gusts that might swirl smoke around inside.

Without knowing its archeological context, this rock would simply be considered a natural sandstone slab.

The sandstone slab air deflector as it was found near the central hearth (not yet excavated) in Drover’s house. The large sandstone slab was placed vertically and set into the house floor. The view is toward the east, where the entryway was located. The undulating orange, black, and brown materials represent fired daub and heated earthen fill from the roof, having fallen onto the house floor when the lodge burned.

The sandstone slab after it was removed from the excavation. It is unmodified, but its archeological context is what revealed its important function inside Drover’s house. Its location and orientation, set vertically into the floor close to the central hearth, reveals that it was intentionally placed there to serve as an air deflector.